New interview with Johann Knobel about the eagles in Africa

I met Johann Knobel on our last day during a 3 week Africa raptor trip in January 2012. He was our guide on the last day and helped us find a Little Sparrowhawk and an Ovambo Sparrowhawk and a very unusually marked Booted Eagle. Later we drove to the Johannesburg Botanical Garden to watch African Black Eagles.

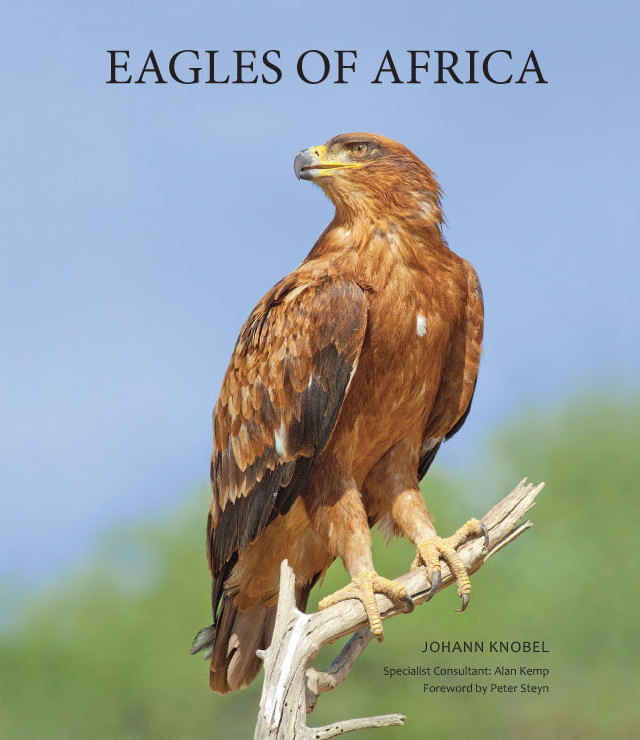

It was clear from the beginning that Johann is very passionate about raptors and has a vast knowledge, particularly about eagles. I was very happy to learn that he was working on a book about African Eagles at that time and I immediately asked him to do an interview about the book and African eagles once the book is finished. The book is now out (see the book’s website at: Eagles of Africa) and it is a wonderful mixture of stunning pictures and a very informative text covering all African Eagles including rare guests like the Spanish Imperial Eagle.

Read this interview to learn more about the book, the work behind it and to learn more about eagles in Africa. Many thanks to Johann for agreeing to do the interview.

Markus Jais, Germany, January 2014.

What is your book all about?

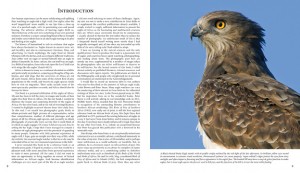

It deals with the 26 eagle species occurring on the African mainland. I try to show just how beautiful and impressive they are, and to tell the story of how utterly fascinating their lives are. Each species is introduced in its own essay with photographs showing various plumages and age groups, and including many action pictures. The species accounts are followed by essays on the hunt, the breeding cycle, the eagle’s day and the eagle’s world. I have tried to combine photographs and text in a way that would make the eagles of Africa accessible and interesting to any reader, from confirmed eagle-watchers right through to people who have not yet seen an eagle in the wild.

How did you get interested in eagles?

When I was a child, many family holidays were spent in the Kruger National Park, which is an eagle paradise. But the single most life-altering influence in this regard was the publication of Peter Steyn’s wonderful book Eagle Days in 1973, when I was eleven years old.

What are the challenges when photographing eagles?

Approaching them sufficiently closely to get a useful picture is often difficult. And to me, it is important to obtain images of their behaviour as well, to show how they live, in addition to producing pleasing portraits of static birds. Flying eagles can be tricky to photograph, and hunting eagles can be particularly elusive. If one is building a collection of photographs for a book on eagles, all the sky backgrounds become repetitive, and it becomes a challenge to photograph at least some eagles against more varied backgrounds.

In Europe most eagles are shy. Are African eagles more approachable?

This varies between species, and often also between individual members of a species. In the parts of Africa with which I am most familiar, one should also differentiate between protected areas and unprotected areas. In national parks and reserves, many eagles are habituated to vehicles, and provided one stays inside the vehicle and behaves with common sense, one can frequently approach these birds very closely. This is fantastic for viewing and photography, and for this reason much eagle photography in Africa is vehicle-based. In some well-known tourist areas such as the Okavango Delta in Botswana and the Rift Valley lakes in Kenya, African Fish Eagles are accustomed to be fed by tourist guides, again providing great opportunities for close views and photography, typically from a boat. Outside protected areas, eagles are generally much shyer, although I have known many exceptions to this rule. For instance, on the east coast of South Africa, two African Crowned Eagles have been nesting very close to the entrance gate of a popular golf and holiday estate for several years. The nest tree is right next to the main access road, and every day, countless motor cars and pedestrians pass the nest at close range. Lawnmowers, weed-cutters and maintenance equipment often raise noise levels far beyond what I find bearable, and yet the eagles are quite habituated to all of this.

What was the most difficult picture to get that’s in the book?

I think I should split the answer up into three parts:

First, the species that was the most elusive: the Ayres’s Hawk-Eagle, or Ayres’ Eagle. I had to wait and wish many years for an opportunity to take decent photographs of it. In an ironic but happy twist of fate, I obtained my best shots of the Ayres’ in Pretoria, where I have lived all my life, at the eleventh hour as the production of the book was drawing to a close.

Second, I also had to wait very long to get pictures of certain kinds of eagle behaviour. Mating comes to mind as a particularly difficult activity to photograph. In the end I obtained reasonable shots of Black-chested Snake-Eagles mating, but within three months of Eagles of Africa reaching the book shops, I took better pictures of African Hawk-Eagles mating. Getting a photograph of an eagle bathing also eluded me for an incredibly long time. Eventually I got lucky with an African Fish Eagle bathing in the Letaba River in the Kruger National Park.

Third, the photographs for which I suffered the most: a comparatively common species, the Wahlberg’s Eagle, at its nest. Through the generosity of the well-known South African ornithologist Warwick Tarboton, and our mutual friend Mich Veldman, I could use a hide on an eight-metre high aluminium tower to photograph a very photogenic Wahlberg’s Eagle nest. This particular pair was special because the male was a dark morph bird and the female was a pale morph one. The only problem was my fear of heights. Sitting in the apex of that wobbly structure, with Eurasian Bee-eaters catching flying insects far below me, scared the living daylights out of me. I have the greatest admiration for bird photographers who do that kind of thing as a matter of routine.

What are the main threats to eagle conservation in Africa?

The most serious threats are similar to those faced by eagles in many other parts of the world: habitat destruction; depletion of the prey base; direct persecution; and indirect poisoning (where poisoned bait is left for other species such as jackals, caracals, feral dogs or leopards). Electrocution and collision with electricity structures are also factors in some areas. South Africa will see the introduction of many wind farms in the near future, and these will inevitably claim some eagles. Ornithologists have been involved in planning and impact studies from an early stage, and we hope that this will mitigate the impact on birds. A massive wind energy project is planned for Lesotho, and our main concern here is for highly threatened Bearded Vultures and Cape Vultures, but some eagles may also be at risk.

In South Africa, three eagle species have, in particular, suffered alarming range reductions and/or reductions in numbers: Bateleurs, Tawny Eagles and Martial Eagles. Carrion is an important food source for Bateleurs and Tawny Eagles, and the decline of these two species is probably mainly related to their finding and eating poisoned bait illegally put out for mammalian predators. Martial Eagles have traditionally been suspected as lamb catchers, and their decline is probably mainly related to direct persecution. Of the African resident species, the Southern Banded Snake Eagle has the smallest distribution range. It is basically restricted to a thin strip of tropical bush on the African east coast, and is therefore very vulnerable to habitat destruction. The Sahel savanna habitat of the Beaudouin’s Snake Eagle is also under pressure, and this species is listed as Vulnerable in the IUCN Red List, which makes it the resident African eagle species with the gravest Red List status. The other species I have mentioned here are all classed as Near-threatened, except for the Tawny Eagle, which is still of Least Concern on a continental and global scale.

A threat to vultures, in particular, is targeted killing by lacing carcasses with poison, either to obtain vulture body parts for use in traditional medicine, or to mask the activities of ivory poachers, who worry that the presence of vultures in the skies will reveal the whereabouts of their illegal activities. Scavenging eagles also succumb to such vulture-targeted poisonings.

What is the most endangered eagle species in Africa?

Of the species breeding in Africa, I would think that the Beaudouin’s Snake Eagle and the Southern Banded Snake Eagle are the most vulnerable. However, we should keep a close watch on all five eagle species mentioned in the previous answer, and just recently the African Crowned Eagle has also been up-listed to Near-threatened by BirdLife and the IUCN. Big savanna parks and wilderness areas still hold appreciable numbers of Bateleur, Tawny Eagle and Martial Eagle, but some evidence is emerging that populations in protected areas may not be quite as secure as we may have hoped for. Very little information is available on the Congo Serpent Eagle and the Cassin’s Hawk-Eagle, but they are not suspected to be in trouble in the shorter term. As you well know, there are concerns about some of the migrant eagles that visit Africa from Europe and Asia, with the Eastern Imperial Eagle and the Greater Spotted Eagle immediately coming to mind. The rarest of all the eagles on the African list is certainly the Spanish Imperial Eagle. Although it was historically a breeding resident in Morocco, it is to the best of our knowledge only a rare non-breeding vagrant to Africa at the moment. One can only hope that Spanish conservation efforts will eventually prove so successful that more Spanish Imperial Eagles will once again venture into Africa.

What do you think should be done to secure the future of the eagles in Africa?

In an Africanraptors.org interview with Alan Kemp about the conservation of the Martial Eagle, Alan said that the most important step is to maintain as many large pristine or near-natural areas as possible, and I agree whole-heartedly with this. In Africa we are blessed to have some magnificent parks and wildernesses, and most of them are well-populated by eagles. However, much of Africa is densely populated by humans, and setting aside protected land can only be part of the answer. We also need to mitigate threats to eagles where they range outside protected areas, to address aspects such as direct persecution, poisoning, and habitat destruction. Migratory species pose special problems, and the Memorandum of Understanding on Migratory Birds of Prey in Africa and Eurasia, established in the wake of the Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, is aimed at addressing these problems. The law can play an important part in the conservation of raptors, and I have embarked on research on how the law can be used more effectively to protect raptors in Africa, with the emphasis on eagles. Many people tend to think that the most important role of the law in nature conservation is to punish people for transgressions, but the law can also provide for positive actions that can benefit eagles and other wildlife, such as creating protected areas, and mandating and facilitating environmental impact studies and biodiversity management plans. Environmental laws can also help to inculcate a culture of respect for, and national pride in, the natural heritage of a nation. The most inspiring example for all of us is probably a European one, namely the holistic and creative use of European Union laws and Spanish laws to initiate and facilitate the conservation of the Spanish Imperial Eagle. On the other hand, over-regulation is also a danger that must be guarded against. In South Africa, a very positive conservation initiative is the cooperation between the national electricity supplier and the Endangered Wildlife Trust to mitigate bird mortalities on electricity structures, and this was entered into voluntarily with no legal coercion. The Endangered Wildlife Trust also does wonderful work to promote favourable attitudes towards eagles in farming communities. More important than achieving compliance with the law, is changing the hearts of people, of winning human friends for the eagles of Africa.

Most news about wildlife conservation in Africa is currently about Elephants, Rhinos and Lions. This is of course important, but do you think that eagles don’t get enough press?

I would agree with that, but I should also openly declare my bias as an eagle fanatic. Rhinoceros poaching is really a national crisis in South Africa at the moment, and it is understandably taking the limelight. Of all the raptor groups, the greatest concern is for the vultures. The outlook for them is bleak, as they are highly mobile, and poisoned carcasses can kill large numbers of them even though they may, for instance, breed inside large national parks. Conservation NGOs like the Endangered Wildlife Trust are doing great work to inform the public about the plight of vultures. Eagles tend to play second fiddle to some extent, and I can understand this very well, but I would like to see them getting more publicity.

How can eagle photography help protect the birds?

Great question! If people love eagles, they want them to be protected. Many people seldom, if ever, see an eagle really well, and how can they love something that they do not know? Eagle photographs have the potential to bring eagles closer to such people. Just the other day, someone who paged through my book remarked that she had never known that eagles were so beautiful. Eagles really need human friends today. I hope that eagle photographs, eagle books and films, and websites such as this one and the Global Raptor Information Network and the europeanraptors.org site, would be able to win more human friends for the eagles and other raptors.

How should a responsible bird photographer behave in the field in order to not disturb or harm the eagles?

If the photographer loves the birds more than photography, he or she will usually intuitively do the right things. It is important that one’s desire to obtain a certain photograph does not overshadow one’s sensitivity for the well-being of the eagle. Photography at a nest brings with it a special responsibility. I am not aware of any African laws prohibiting photography of birds of prey at their nests, unlike the position, for instance, in some European jurisdictions. The photographer’s conscience must therefore be the guide to proper conduct. If an eagle pair does not accept the presence of a photographer or a hide/blind near the nest, the photographer must abandon the attempt at photography and leave the birds in peace. Also, one should never erect a hide/blind in a spot where it is likely to attract the attention of humans who may intentionally or inadvertently disturb the breeding birds. Away from the nest, the stakes are not quite so high, but one would do well not to chase an eagle off its hard-won prey, or to disturb it in its night-time roost. In Africa, the larger national parks and game reserves give the photographer the opportunity to photograph many eagle species, and provided the photographer heeds the rules applicable in the park, and uses common sense, the potential of serious disturbance to the eagles is small.

Do you have some tips for bird watchers and nature photographers who want to take stunning images of eagles?

This ties in nicely with the previous question. I think the best advice is to love your subjects, the eagles, more than your equipment and the photographic process. I believe that that kind of dedication will shine through the photographs in the end. All the usual nature photography tips about good light, composition and backgrounds are relevant to eagle photography, although eagles often make things difficult by exhibiting the most interesting behaviour in the hottest part of the day when the light can be very harsh in many parts of Africa. One thing that many photographers overlook when photographing perched raptors, is the pose of the bird. An eagle just standing there, although it is a magnificent creature, can make a rather boring photograph. Wait for it to be alert on sighting prey, or before taking flight, because then it will often stand in a bolder and more photogenic stance. An insider tip already known to many bird photographers, is that an eagle will often defecate before taking flight, and this can be the photographer’s cue to be ready for a burst of action photographs.

A very personal thing: I do not like the look of many photographs of eagles where electronic ‘fill-flash’ was used to supplement natural light. The flash tends to eliminate the small shadow under the heavy ‘eye-brow’ of the eagle, and this often results in the eagle looking startled instead of fierce. To me this robs the photograph of its soul. l prefer to use natural light only, and to lighten the shadows somewhat in post-processing.

People are always interested in other photographer’s equipment. What do you currently use?

I am a somewhat conservative equipment buyer, and I ‘upgrade’ my eagle experiences far more often than my equipment. I estimate that roughly a third of the photographs in Eagles of Africa were taken with film cameras, but these days I use digital cameras only. I use two DSLR camera bodies, and both are so-called ‘crop-frame’ rather than ‘full-frame’ cameras. The full-frame bodies are known to produce superior image quality, especially in low-light situations. However, I usually find my subjects in bright light, and my main challenge is usually the ‘reach’ of my lenses. In such situations, the crop-frame bodies seem to work very well. For flying eagles, I usually use a 300 mm lens, more often than not in conjunction with a 1.4x converter, and I prefer to hand-hold the camera to follow the movement of the target. When working from a vehicle, I often prefer a fast 300 f2.8 lens, but I also use a much smaller 300 f4 lens if portability is a priority. I use an old 600 mm lens for perched birds, birds on nests, and birds that are taking off or alighting. The 600 mm lens is also often used with a 1.4x converter, and is always supported on a bean bag or a tripod.

.

Do you have a favourite place to photograph eagles?

Yes, the Kruger National Park. I have loved it since my childhood holidays, and it remains the only place where I have managed to see 10 different species of eagle in a single day. However, the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park is stiff competition from a photographic point of view, as it has the advantages of a greater percentage of sunny days and more open terrain, making action photography easier. Neither the Kruger nor the Kgalagadi is good for photography of some of the most spectacular eagle species, for instance the (African) Crowned Eagle, and Verreaux’s (African Black) Eagle, so there is always a need to visit other special places too.

Do you have a favourite eagle species?

Yes, my favourite eagle species is the one I am looking at through my binoculars or camera at any given moment.

What photography plans do you have for the future?

After completing Eagles of Africa, I told my wife that I really looked forward to be less obsessed with eagles and to enjoy photographing other birds and wildlife again. We went to the Kgalagadi soon thereafter, and guess what? As soon as we began to find eagles, all other species paled into insignificance. So I guess my photography plans are to photograph as many eagles as possible without the pressure of trying to fill the pages of a book.

How do you see the future of eagles in Africa?

As Alan Kemp said in his interview, the real challenge is how to conserve raptor and raptor habitat in view of the needs and aspirations of the growing human population of Africa. This is indeed a daunting task, but we shall not be able to make a difference for the eagles of Africa if we are paralysed by pessimism. Certainly there is a lot to feel gloomy about, but Africa is still a great continent for eagles. We must be neither despondent, nor complacent. We must be vigilant, and we must be positive that we can make a difference for the magnificent winged predators of Africa. Ultimately, I believe, the children of the African people will also be happier if the African skies are still graced by soaring eagles.

What was your most amazing experience with eagles?

Watching the tiny bill of a Verreaux’s (African Black) Eagle chick breaking through a tiny hole in an egg was a highlight. I like to think of that experience as having witnessed the birth of an eagle. Watching the breath-taking aerobatics of displaying Booted Eagles and hunting Ayres’ Eagles has also been exhilarating. A thousand Lesser Spotted Eagles congregating at a nesting colony of Red-billed Queleas in the Kruger National Park was a fantastic spectacle. But the best experience was probably finding an exceptionally confiding juvenile Martial Eagle. I could approach it so closely in my vehicle that, every time I took a picture, the eagle turned its head from side to side on hearing the camera shutter. For a change, the eagle appeared to be just as interested in me as I was interested in it! The story is told in the last chapter of Eagles of Africa.

I must add that the people who assisted me in various ways while I was working on Eagles of Africa, were also truly amazing. Many special friends and landowners were astoundingly helpful and hospitable. Many of the well-known ‘eagle people’, from Africa and abroad, also helped me: Alan Kemp (mentor and scientific adviser), Peter Steyn (inspiration, mentor and writer of the Foreword), Bill Clark, Rob Davies, Dick Forsman, Rob Martin, Rick Watson, and many others. To have shared in their knowledge and experience so freely, was also an amazing experience. Finally, I would like to say thank you, Markus, for helping me with advice on where to find the Spanish Imperial Eagle while I was still working on my book, and for this opportunity to talk about the eagles of Africa on your website.

Thank you Johann for answering all the questions!

To learn more about the book, see here:

Eagles of Africa