Montagu’s Harrier research in the Sahel

Below is an exciting account of the work conducted on Montagu’s Harriers in the Sahel by the Dutch Montagu’s Harrier Foundation. Special thanks goes to Christine Trierweiler for providing the information and photographs.

Aims of our Montagu’s Harrier work in the Sahel

We started our work in January-February 2006. Our aims are:

a) to collect information on distribution, abundance, habitat use, behaviour, diet, and prey abundance of Montagu’s Harriers in their W-African winter quarters, and threats to these, so that protection strategies for this species in Africa can be improved.

b) to co-operate with, and train, local counterparts, and thus help improve local bird conservation research.

These aims are similar to the aims of the Foundation within The Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe.

Summary of first findings

Our research methods included raptor counts along roads while driving, prey counts along transects on foot, and collection of pellets at harrier roosts (detailed methods see appendix).

Habitat use and threats to preferred habitats

The data we collected in Niger in January 2006 show that Montagu’s Harriers prefer shrubland and tigerbush habitats. These habitats were richest in grasshoppers, their main prey species. Habitats with a higher density of trees were not selected. In treed habitats, bird prey was more abundant, but grasshoppers were less abundant than in the open landscapes. Montagu’s Harriers appeared to prefer less degraded over heavily degraded habitats. In Niger, about half of the sampled shrubland and tigerbush habitats showed signs of serious degradation.

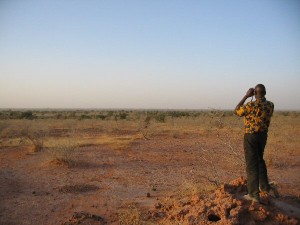

Possible causes for degradation were overgrazing, cutting of live firewood (which is prohibited), and climate change, eventually leading to erosion or desertification. We fear that the natural habitats of Montagu’s Harriers are threatened with disappearance by the increasing human population pressure on these natural landscapes. During our first mission, we witnessed the consequences of heavy land use in Burkina Faso: diversity of habitats and the abundance of birds seemed to be much lower than in less degraded areas in Niger.

We cannot predict whether Montagu’s Harrier will be able to adapt to agricultural land, like the species did in most of Western Europe after losing its natural habitats there. However, the large flexibility of the species concerning habitat and prey selection in Europe makes us suspect that the harriers may be able to cope with some degree of environmental change in its wintering areas, too.

Diet

Based on observations in Senegal and India, it has been suggested that locusts are an important food source for Montagu’s Harriers in their wintering areas (Cormier & Baillon 1991, Clarke 1996 a, b). However, locust-feeding birds probably depend on resident grasshopper species in years when locusts are not abundant (Brouwer et al. 2003, W.C. Mullié pers. comm.). Our findings support this latter hypothesis. However important resident grasshoppers may be for Montagu’s Harriers in average years, we expect that locusts like Schistocerca gregaria will dominate the harriers’ diet in years with high locust

abundances. In plague years, locusts have made up 84 % of the harriers’ diet in Senegal (Cormier & Baillon 1991). Locusts are not always a safe food resource: in plague years, pesticides sprayed against them can increase mortality of locust-feeding birds (Mullié & Keith 1993, Cormier & Baillon 1991,

Clarke 1996a). We conclude that locusts as a poisoned food source are a threat to wintering harriers in locust plague years, but most likely not in average years.

Raptor persecution

The satellite-tracked Montagu’s Harrier female ‘Marion’ (www.grauwekiekendief.nl) was killed by a Nigerian farmer who intended to protect his poultry from raptors. The fact that she wore a transmitter made it possible to reconstruct her fate. Practices like capturing raptors at their roosts at night seem to be widespread in Niger and Nigeria, as farmers assume that all raptors prey on poultry. The farmer concerned said that Marion was captured together with two unmarked Montagu’s Harriers. Two ringed Ospreys from Finland were handed to the authorities in the same district of Nigeria during the same month. Very likely many more unmarked raptors were captured and killed in this same short time span. We believe that a considerable part of the mortality measured during wing-tag and ringing programs of migratory raptors can be explained by persecution. Killing wild birds does not stop at raptors. As we witnessed ourselves, water birds at wetlands are often hooked on fish lines, either as by-catch during fishing or on purpose for consumption. We think that sensitization of farmers to the importance of wild birds, and of raptors in particular, may be a first step to better winter survival of migrants. Farmers we met reacted positively to the information we provided, and were interested to learn that, for example, Montagu’s Harriers mostly prey on locusts, not on poultry. The presence of harriers in agricultural land may thus even be beneficial to farmers. In India, local people know the possible benefits of locust-consuming raptors for agriculture and even include this knowledge in their folklore.

Literature cited

Arroyo, B.E., King, J.R & Palomares, L.E. 1995. Observations on the ecology of Montagu’s and Marsh Harriers wintering in north-west Senegal. Ostrich 66: 37-39.

Brouwer, J., Mullié, W.C. & Scholte, P. 2003. White Storks Ciconia ciconia wintering in Chad, northern Cameroon and Niger: a comment on Berthold et al. (2001). Ibis 145: 499-501.

Clarke, R. 1996a. Montagu’s Harrier. Chelmsford: Arlequin Press.

Clarke, R. 1996b. Preliminary observations on the importance of a large communal roost of wintering harriers in Gujarat (NW. India) and comparison with a roost in Senegal (W. Africa). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 93: 44-50.

Cormier, J.-P. & Baillon, F. 1991. Concentration de busards cendrés Circus pygargus (L.) dans la région de M’bour (Sénégal) durant l’hiver 1988-1989: Utilisation du milieu et régime alimentaire. Alauda 59(3): 163-168.

Mullié, W.C. & Keith, J.O. 1993. The effects of aerially applied fenitrothion and chlorpyrifos on birds in the savannah of northern Senegal. Journal of Applied Ecology 30: 536-550.

Appendix: Methods

Raptor road transect counts

Two teams of each three potential observers share one 4×4 vehicle. Road transects are counted at an average speed of 60 km/h, if possible (sometimes impossible on dirt or sand roads). All raptors seen from the vehicle are noted, if possible species, sex and age. This method has been described by J.-M. Thiollay (Ibis 148: 240-254, 2006).

Additionally, we note the behaviour and habitat of the observed raptor (for habitat types). For Montagu’s Harriers, we stop, take a GPS waypoint, and try to observe and note the behaviour as long as possible. These ‘loose observations’ are noted separately from the road transects. Often, harriers occur in loose associations of several individuals, indicating that they roost in the vicinity. One can return to the spot one hour before sunset and try to locate the roost. Furthermore, we determine during the road transects the habitat type at one point (each side of the road) every 5 km, in order to establish whether the observed raptors select certain habitat types. With the habitat type, also a degradation score is noted (see form below). Road transects vary between ca. 50 and several hundred km in length. Observations made between 12:00 and 15:00 h are not included, as we found that no Montagu’s harriers are seen during these hours, probably because they seek refuge from the heat then.

Harrier prey transect counts

In order to estimate food abundance per habitat type, we choose relatively homogenous areas of the same habitat for prey transect counts. Prey transect counts can vary from 30 m to over 1 km in length. The observer notes birds within 20 m to the left and 20 m to the right (this method is also used by A&W

ecological consultants, The Netherlands, during research in West Africa). Birds flying over are noted separately. Small mammal holes 2m left and 2m right from the observer are counted, allocated to one of two size classes (see form below). Grasshoppers are counted 2m left and 2m right from the observer, sorted in 4 size/colour classes. Other potential harrier prey items like reptiles are also noted. At prey transect locations, reference samples of occurring grasshopper species are collected. Habitat characteristics are noted as well (height of grass estimated with a ruler, height of shrubs and trees estimated visually, tree density per hectare estimated visually). The beginning and end of the transect is marked by GPS in order to calculate transect length and surface area afterwards (length x 40 m for birds, length x 4 m for mammal holes and grasshoppers).

Hi, could you please get me in touch with this research group? best regards,

Attila