Conservation of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus meridionalis. By Sonja Krüger

Introduction

The Bearded Vulture is listed as endangered in the Southern African Red Data Book due to its small and declining population size, restricted range, range contraction, and the susceptibility to several threats in Lesotho and South Africa (BirdLife, 2004). Its red data status and the lack of data on current population size lead to a monitoring programme being implemented in 2000 by Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife to determine the number of breeding pairs in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa.

Results from the initial surveys in KwaZulu-Natal and subsequent surveys in the rest of the Bearded Vulture’s range in the Free State and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa and in the Kingdom of Lesotho, suggested a significant decline in the number of breeding pairs throughout its range and concern as to the viability of the species as a whole in southern Africa.

A Population Habitat and Viability Analysis (PHVA) workshop was held in 2006 to model the probability of extinction of the southern African Bearded Vulture population (Krüger et al., 2006). Since there was a probability that the species would be extinct within 100 years, it was essential to identify threats to the species and come up with solutions to address the threats which would ultimately reduce the modeled population decline.

A Bearded Vulture Task Force was formed under the banner of the Birds of Prey Working Group of the Endangered Wildlife Trust. The aim of the task force was to ensure that the resolutions of the PHVA workshop were implemented. The task force consists of members from Lesotho and the three provinces of South Africa within the breeding range of the Bearded Vulture. In 2007, Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife and the Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Project launched the Maluti-Drakensberg Vulture Project to ensure that funding was made available to protect the Bearded Vulture that was seen as an icon of the transfrontier project.

All research and conservation actions implemented by the Bearded Vulture Task Force and the Maluti-Drakensberg Vulture Project aim at gaining a better understanding of the species in order to improve their conservation status.

One of the most important actions identified during the PHVA process was to determine the threats to the species within their home range and the causes of their mortality. This action led to the implementation of a satellite tracking project.

The Ranging Behaviour of Juvenile Bearded Vulture

In 2007, three juvenile Bearded Vulture were caught at a feeding site and fitted with satellite tracking devices. One of the devices, fitted to a 1-2 year old female, stopped transmitting within the first month and was never recovered. The second device, fitted to a 3-4 year old male, was removed by the bird after 10.5 months. The third bird, a 1-2 year old female, was found dead in Lesotho after nine months. Poisoning was the suspected cause of death. The home range of the latter two birds was determined using the Minimum Convex Polygon method. The male had a home range size of 25 000 km2, and the female had a home rage size of 34 000 km2.

In 2008, two nestlings were fitted with satellite transmitters. The first bird was a female that was found poisoned in the Eastern Cape, six months after fledging. The second bird, also a female, is still providing interesting data on her ranging behaviour. Both birds slowly increased their home range area after fledging with the first female having a range of 16 619 km2 after six months and the second female having a range of 29 100 km2 after 15 months.

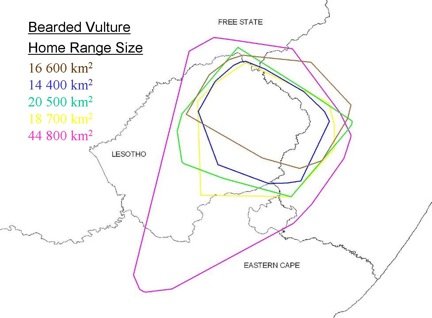

During August 2009, five bearded vulture were caught at a feeding site and fitted with satellite transmitters. The two males and two females were 1-2 year old birds and one male was a 2-3 year old bird. The home range sizes of the younger birds ranged from 14 400 km2 to 20 700 km2 within the first seven months of them being tracked, and the home range size of the older bird was nearly twice the size in the same time period (see Figure 1). The birds are all still transmitting ranging data and are moving extensively across Lesotho and parts of KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, occasionally venturing into the Free State.

A juvenile Bearded Vulture was found dead after colliding with a powerline in KwaZulu-Natal in September 2009, the third bird to have been killed in this way in the past 10 years. It is likely that powerlines kill more vultures than we know of because finding carcasses in remote areas is virtually impossible.

Conclusion

The satellite tracking information to date has provided interesting information on the spatial and temporal movement patterns of young Bearded Vultures as well as the causes of mortality in two cases.

The project has identified poisoning and collision with powerlines as the two most important threats facing the species. These threats were also identified by Brown (1988) although the reasons for poisoning may have been different then.

In order to obtain more accurate results, it is essential to increase the sample size of Bearded Vulture that are fitted with satellite transmitters, to include adult birds in the sample, and to obtain long term data on their movement patterns.

However, in the meantime, the home range data will be used to identify areas of frequent use. These areas will be the focus of mitigatory action in terms of assessing powerline risks and the potential for poisoning or persecution of the birds. Mitigatory action that is being implemented includes adding raptor protection devices to electricity poles and diversion devices (flappers) to the lines, awareness programmes focusing on alternatives to the use of poison for controlling predators, and addressing the use of birds for traditional medicine through education programmes.

With the successful implementation of these and additional programmes, and implementation of conservation actions, we hope to reverse the population decline to ensure that future generations can benefit from watching these monarchs of the Maluti-Drakensberg mountains.

References:

BirdLife International (Eds). 2004. Threatened Birds of the World. BirdLife International/Lynx Edicions, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Brown, C.J. 1988. A study of the Beaded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus in southern Africa. PhD thesis, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg.

Krüger, S., Piper, S., Rushworth, I., Botha, A., Daly, B., Allan, D., Jenkins, A., Burden, D., Friedmann, Y. (editors). 2006. Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus meridionalis) Population and Habitat Viability Assessment Workshop Report. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC / IUCN) / CBSG Southern Africa. Endangered Wildlife Trust, Johannesburg.

Sonja Krüger

Ecologist, Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife

PO Box 13053, Cascades, 3202, South Africa,

e-mail: skrueger@kznwildlife.com

Acknowledgements:

The project has been sponsored by the Wildlands Conservation Trust, Sasol through the Endangered Wildlife Trust, the Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Project, Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, Apsen Pharmaceuticals and Fundacion Terra Natura.

I wish to know about the bearded vulture’s habitat adn other information. Population and Habitat Viability Assessment Workshop Report. Thanks

Hi,

I have seen the Bearded Vultures nesting at Witsieshoek. They are without a doubt one of my favorite BOP. I have practiced falconry for almost forty years. We as falconers are dedicated to conservation and rehabilitation.

Regards

Julius Ramsay