Madagascar Fish Eagle Interview with Ruth Tingay

I first met Ruth Tingay at the American Ornithological Society meeting Boise, Idaho in 1996, and then again at the World Working Group for Birds of Prey conference in Midrand, South Africa in 1998. At the time, The Peregrine Fund was well into its research and conservation project on the Madagascar Fish Eagle, and we had developed questions about the strange breeding behavior of the species that I recognized could only be answered with behavioral and genetic research by someone with exceptional focus, drive, and tenacity. I also knew that a sense of humor and an ability to turn adversity into adventure would go a long way toward coping with the challenges of working in one of the least developed countries in the world. Ruth demonstrated that she had the drive and tenacity as she relentlessly pursued her interest in raptor research at the conference; and through several conversations that week, she struck me as someone who would do well in Madagascar. Within a year, she had organized a place in a Masters-degree program at the University of Nottingham, and joined our fish eagle team in western Madagascar.

Ruth’s humor was essential to her survival in Madagascar, as you will grasp from this excerpt describing her first trip to the study site: “Our journey continues at dawn as we travel north to the first river crossing, where a ‘restaurant’ serves cold drinks and boiled fruit bat. A seven-hour wait (usually it’s only four) until the ferry arrives and we board the wooden platform that has been nailed to some oil drums for flotation purposes. Another night in a hotel across the river, where I’m lucky enough to get a room at the front so I can enjoy the all-night disco without having to pay an entrance fee. A cold shower and an old mattress shared with fleas and cockroaches heralds the threshold into the glamorous world of fieldwork in Madagascar.” Undeterred, her entertaining and illuminating “Notes from the field” continued through several years of study on the Madagascar Fish Eagle for both her Master’s and Doctoral degrees, and can be enjoyed on The Peregrine Fund’s website at http://blogs.peregrinefund.org/author/51.As you will read in Ruth’s interview below, she tackled complex questions with precise field observations and careful genetic analyses, and advanced our knowledge of Madagascar Fish Eagle biology and behavior by several orders of magnitude. Ruth has progressed rapidly from her formative years in raptor research to tackle other challenging projects, such as studying the ecology of Grey-headed Fish Eagles on Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia, and creating, with Todd Katzner, a fascinating compendium of rarely told stories in The Eagle Watchers (Cornell University Press, 2010). She has risen in the ranks of the Raptor Research Foundation (RRF) to current President, where she is spearheading the internationalization of this professional society of raptor researchers (http://raptorresearchfoundation.org/). Organizing the first offshore (outside of the United States) annual conference of the RRF in Scotland in 2009 was a significant accomplishment in so many ways. It has been a pleasure getting to know Ruth, watching her skills develop, and hearing about her often surprising exploits in pursuit of her passion for raptor research. I look forward to working with Ruth on a book about the Madagascar Fish Eagle project, and can’t wait to see what she does next! If you’re fortunate enough to meet Ruth sometime, buy her a “G&T,” ask her about Madagascar—and be prepared to be entertained and amazed till dawn! – Rick Watson, Vice President of The Peregrine Fund.

1) When has the Madagascar Fish Eagle (Haliaeetus vociferoides) separated from other sea eagle species and evolved into a new species? What are it’s closest relatives from an evolutionary point of view?

According to genetic research by Michael Wink & Hedi Sauer-Gürth, Madagascar was probably colonized by an ancestor of the African fish eagle (AFE), which became isolated and developed into the Madagascar fish eagle (MFE) about 2.5 million years ago. According to researchers Ingrid Seibold & Andreas Helbig, and later Heather Lerner & David Mindell, the Haliaeetus genus is neatly divided into those with a northern distribution and those with a tropical distribution. Thus, the MFE is considered more closely related to the AFE, White-bellied sea eagle and Sanford’s sea eagle than it is to the white-tailed sea eagle, bald eagle, Pallas’ fish eagle and Steller’s sea eagle. Lerner & Mindell also suggest the AFE and MFE are sister species, a relationship supported by their unique reddish plumage and complex melodious vocalisations.

2) Where in Madagascar does the Madagascar Fish Eagle occur and which habitat does it need?

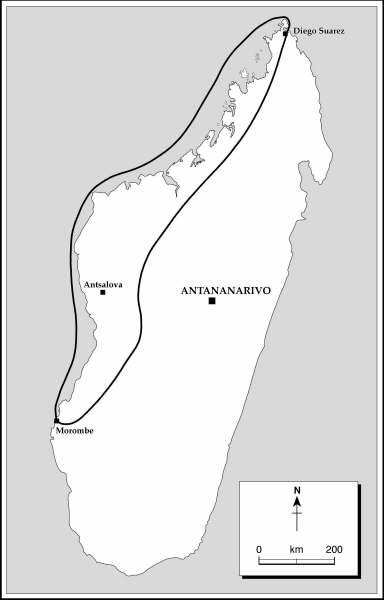

The MFE’s range includes most of the western seaboard (apart from the SW), from Morombe in the south to the island of Nosy Hara in the north (see Fig 1), in coastal habitat and also habitat up to 100km inland. Coastal habitat includes estuarine mangroves, sea cliffs, small islets and sheltered coastal bays. The inland habitat is predominantly dry, tropical deciduous forest close to freshwater lakes and rivers.

3) What is known about the population development during the last decades? Has it always been a rare species?

According to historical records, the MFE was once considered a common species with a broad distribution throughout Madagascar. In the early 1980s, several researchers claimed the species had undergone a “violent decline during the last 50 years” and the species was subsequently listed by IUCN as ‘threatened’ in 1988, and then later upgraded to ‘critically endangered’ in 1994. However, my research has demonstrated that the historical accounts include unsubstantiated reports about the species’ former distribution and abundance, and I found no evidence to support any change between the MFE’s historical and contemporary distribution, abundance and status, restricted to the western seaboard. Further, in collaboration with geneticist Jeff Johnson, we published a paper last year that demonstrated the MFE has maintained a small effective population size for hundreds to thousands of years. The MFE exhibits extraordinarily low levels of genetic diversity, even for an island endemic, but nevertheless, this low genetic diversity is not the result of a recent population bottleneck (at least not within the last 50-100 years as claimed by earlier researchers), thus we concluded the MFE is a naturally rare species with a low but stable population.

4) How many Madagascar Fish Eagles are there in the wild in 2010?

It’s impossible to give an exact figure, given the size and relative inaccessibility of parts of the species’ range. In 1997, The Peregrine Fund published a national population estimate of 99 breeding pairs (95% confidence interval = 78 – 120 pairs) based on surveys they conducted between 1991 and 1995. No further population estimates have been published, although on-going annual monitoring at a proportion of sites suggests little or no change to population stability. It’s probably fair to assume a total population size (adult breeders, adult non-breeders, juveniles) of approx. 300 individuals. However, in the case of the MFE, it is perhaps more interesting to look at effective population size, as opposed to actual population size. As mentioned above, the MFE has exceptionally low genetic diversity; in other words, many MFE individuals share identical genes. My research with Jeff Johnson demonstrated that the MFE’s effective population size (i.e. the average number of individual MFEs that actually contribute ‘diverse’ genes to succeeding generations) is only ~24 breeding individuals (range = 12 – 60 depending on methods & 95% confidence intervals). This is of conservation concern, as although this low effective population size has been maintained for hundreds of generations, the current rate of environmental change within Madagascar is likely to produce potential stressors that the MFE has not previously encountered. The species’ evolutionary potential to adapt to these changes is probably somewhat compromised by its exceptionally low genetic diversity. However, this research was based only on MFE blood samples from the Antsalova population. It did not include data from the NW population, where the presence of additional unique alleles (see question 10 below) may increase the effective population size, although probably not significantly.

5) What is the eagle’s main prey?

The MFE is a fish-specialist, much like the osprey. Research undertaken by Jim Berkelman demonstrated that inland MFEs caught nine different fish species (7 exotic and 2 native), although their preference was for introduced Tilapia spp., an abundant and easily-captured prey item. Dietary preferences of coastal MFEs have not been explored with such rigour. MFEs engage in kleptoparasitism, commonly stealing fish from yellow-billed kites, Humblot’s herons and grey herons. There are a few rare observations of MFEs eating crabs and turtles and attacking domestic ducks.

6) Is there competition with other birds for food or nesting places?

The inland MFEs share their resource needs (nest and perch-trees, and fish) with a variety of other avian species, such as yellow-billed kites, reed cormorants, African darters, Grey herons, Humblot’s herons, purple herons, African open-billed storks, yellow-billed storks and African spoonbills. However, it’s not competition with the avian species that causes the problem – it’s human resource competition. Local fishermen use the large trees for pirogue (boat) construction, pirogue paddles, firewood, traps, honey collection, medicine, coffin construction and house-building. In some areas of the NW coast, MFEs are in direct competition for space with fishing-industry and tourism-related activities, particularly with the recent increase in hotel construction sites.

7) What are the main threats the species faces?

The Peregrine Fund has identified a suite of threats, both direct and indirect. Direct threats include the deliberate destruction of nests and young, the theft of nestlings for food, shooting and trapping of adults, the use of eagle body parts in traditional medicine, and the capture of eagles for pets. Indirect threats include the effects of unsustainable resource use (as outlined above), the alteration of wetlands to accommodate conversion to rice paddies, erosion from upstream deforestation causing high siltation/turbidity of potential foraging habitat, and disturbance from tourism and fishing industries on the NW coast.

8) Are there any current conservation programs for the species?

The Peregrine Fund is the only group actively involved with in-situ MFE conservation activities. Beginning in 1991, they undertook studies on the species’ basic biology and ecology, and subsequently identified the conservation threats. This project continues, almost two decades later, although the focus has since changed from the early years. At the heart of the current project is an award-winning community-based wetland sustainability scheme, whereby local people have been empowered to enforce traditional resource utilization rules to put a halt to the unsustainable activities of migrant fishermen, who were depleting fish stocks and destroying the forest. Not only was this threatening the livelihoods of the locals, but it was also potentially devastating for the long-term survival of the local MFEs. The project location is in Antsalova, west-central Madagascar, in an area that holds at least 10% of the MFE’s global population. The results are remarkable, with workable practices now in place to prevent unsustainable activities such as over-fishing and deforestation, and direct and indirect persecution of MFEs has diminished considerably in this region. In addition, in 1998 the project site was designated as one of the first RAMSAR sites in Madagascar.

9) The Madagascar Fish Eagle has a rather unusual breeding biology compared to other eagles. Can you tell us more about it?

My research suggests that 38% of the MFE’s known breeding population exhibit cooperative breeding strategies. Cooperative breeding appears to occur only on freshwater lakes in the Antsalova region, and the unusual diversity of strategies includes polyandry, polygyny, polygynandry, homosexuality and typical cooperative breeding. Each breeding group is characterised by a linear dominance hierarchy, comprising female(s), primary, secondary and sometimes tertiary males. Group membership and dominance status appears to be relatively stable between breeding seasons. Group members are not necessarily related to one another, although some females and primary males are first-order relatives, and all are adults. They each contribute to the breeding effort, including copulation, nest-building, incubation, food provision, territorial defence and brooding of young. Undispersed juvenile progeny from previous years remain in some territories but do not contribute to the breeding effort.

The dominance hierarchy between males is unusual in that it does not appear to be associated with access to the female or paternity assurance. All males copulate with equal frequency during the fertilization period and dominance interactions between males don’t occur either during or after copulations. Male dominance is mostly associated with access to the nest for the duration of the breeding period, and particularly with stick delivery by the subordinate male(s).

Whilst there are various costs and benefits of cooperative breeding to all group members, the factors encouraging the evolution of cooperative breeding in this species remain unknown, as my research results challenge the main hypotheses used to explain the evolution of cooperative breeding in other avian species.

10) What gaps in our knowledge of the species do still exist? Where should research focus in the future?

Although we have learned a great deal about the MFE in a relatively short period of time, there are still many gaps in our knowledge. Some future research needs are purely academic, but some could be applicable to conservation management for this species. For example, our understanding of the MFE’s breeding strategies is based only on a short-term study. For a long-lived and low reproductive-output species like the MFE, a comprehensive study would take a few decades, at least. However, understanding more about the unusual diversity of these strategies would not only further the intellectual debate about cooperative breeding, but may also provide insight to dispersal strategies, philopatry, mate and site fidelity, and their implications for MFE conservation.

Another topic might include an investigation of the genetic structure of the NW coast MFE population. We have done some preliminary work on this and there are indications that the NW population may be genetically distinct from the Antsalova population, although we didn’t collect enough samples from the NW to investigate the full extent of this. We do know that there are some ‘unique’ genes in both the Antsalova and NW populations, suggesting limited emigration/immigration between these sub-populations – but to what extent and would this suggest that different management strategies are required for each sub-population?

More long-term data are required on juvenile dispersal and survival, and also on adult movements during the non-breeding season, as little is known about these aspects of MFE life history. Two MFE juveniles were satellite-tracked by Simon Rafanomezantsoa in 1997-1998, but the study was limited due to the expense of tags at that time. More tracking data would be helpful for identifying other areas of importance within the species’ range, such as potential ‘nursery’ areas for non-breeding juveniles, and may also help our understanding of territory acquisition, particularly amongst cooperative breeding groups.

11) How do you see the future of the Madagascar Fish Eagle?

MFEs have persisted at low population size for hundreds to thousands of years, and, given their low effective population size, I don’t see any cause for concern in the immediate future, barring any stochastic disasters such as the introduction of a novel pathogen. Indeed, I would argue that their current IUCN status of ‘critically endangered’ (indicating their predicted imminent extinction) is unjustified. However, given the current rate of environmental change in Madagascar, in addition to the long-term and chronic political instability there, the long-term outlook is bleak. Two thirds of the Malagasy population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 USD per day – this gives people a financial incentive to continue the massive deforestation and exploitation of natural resources across the island. Unless a very wealthy benefactor steps in to support a replication of The Peregrine Fund’s work at Antsalova, throughout the MFE’s range, then I think it’s fair to say that the long-term survival of the MFE, like many other Malagasy endemics, is heading in one direction only.

12) In your wonderful book “The Eagle Watchers”, you mention a special male eagle called “Cut Off”. What is his story?

“Cut Off” was a remarkable and very special MFE. He was first trapped as an adult by The Peregrine Fund biologists Russell Thorstrom and Loukman Kalavah in 1996 as they were catching eagles to fit coloured leg bands for individual identification. They found that his right foot was missing, severed at the base of his tarsus, which had since healed over as a flat-based stump. They fitted a band to his left leg and released him. No-one was sure how he’d received his injury, but there were several plausible explanations. He might have been accidentally entangled in a fisherman’s net and had his foot cut off to release him. It’s also possible that his foot was removed for a traditional sorcerer who believed that eagle body parts (especially feet and bill) would provide strengthening properties to a potion. It’s also possible that his foot was removed by locals to obtain a leg band; previously, aluminium leg bands had been mistaken as silver or another precious metal. An alternative explanation might be that he was the victim of a Nile crocodile attack whilst he was bathing or drinking at the water’s edge.

Up to at least seven years later, Cut Off was still in this territory and not only had he survived, but he was the dominant male in a breeding trio. I watched him participate in every aspect of the breeding season, including courtship, copulation, nest-building, incubation, brooding, food provisioning and territorial defence, as well as carrying out regular bouts of dominance attacks on the subordinate male in this group.

I think the reason he managed to survive for so long was because he was able to use his stump to aid his balance. He would catch fish with his left foot and carry it to a favourite tree-perch. He used his left foot to hold the fish in place, and used the stump of his right leg to balance on the branch. This enabled him to lean forward and tear the fish with his beak as normal. During copulation, he appeared to use his outstretched wings and right leg stump to balance on the female’s back. Had his right leg stump been much shorter, I doubt whether he would have been able to distribute his weight as effectively, which would probably have led to sores and infection on his left foot, eventually rendering him unable to hunt.

13) Many people think of the live of an eagle researcher as something a bit romantic. How is reality for an eagle researcher in Madagascar?

For an insight into the realities of eagle fieldwork in Madagascar (and elsewhere), I would recommend reading The Eagle Watchers (Cornell University Press 2010, available in all good book shops!!) which includes field accounts from the western dry forests (MFE) and the eastern rainforests (Madagascar serpent eagle). I wouldn’t describe either experience as romantic! I’m currently working on a book with Rick Watson about the MFE project, which we hope will convey both the exasperation and exhilaration of conducting eagle field research in remote areas of western Madagascar.

14) What other raptors are endangered on Madagascar?

Other resident diurnal raptor species in Madagascar and their current IUCN status are as follows:

Madagascar serpent eagle Eutriorchis astur (Endangered)

Madagascar harrier Circus macrosceles (Vulnerable)

Henst’s goshawk Accipter henstii (Near Threatened)

Madagascar sparrowhawk Accipiter madagascariensis (Near Threatened)

Madagascar buzzard Buteo brachypterus (Least Concern)

Madagascar cuckoo hawk Aviceda madagascariensis (Least Concern)

Bat hawk Macheiramphus alcinus (Least Concern)

Madagascar harrier hawk Polyboroides radiatus (Least Concern)

Yellow billed kite Milvus aegyptius (Least Concern)

Peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus (Least Concern)

Frances’s sparrowhawk Accipiter francesii (Least Concern)

Madagascar kestrel Falco newtoni (Least Concern)

Banded kestrel Falco zoniventris (Least Concern)

15) What was your most amazing experience with Madagascar Fish Eagles?

The most memorable was probably a near-death experience in a boat off the NW coast. Four of us were doing an MFE survey along 400km of coastline, which was expected to take about 4 weeks to complete. We were a couple of weeks into the survey and we’d already had multiple problems with the small fiberglass boat, including engine breakdown, steering breakdown and fuel-line issues. We were heading for a small village to set up camp for the night, but we had to cross the Loza Bay to get there. Crossing the bay should take just under an hour in good sea conditions.

Due to the on-going boat problems, we were late arriving at the mouth of the bay and it was just about to get dark. The sea had become quite rough and I didn’t fancy a night-crossing, so I suggested we set up camp for the night and attempt to cross the bay early the next morning at first light. I was out-voted by the other three, one of whom (local Peregrine Fund biologist, Rivo Rabarisoa) had completed the same survey route with Rick Watson three years earlier.

No sooner had we left the relative shelter of the coastline to enter into the open water of the bay, we were in trouble. Atrocious high seas, compounded by limited night vision, found our imperiled boat precariously bobbing around with all the stability of a soap dish. I was perching on a fuel container towards the front of the boat while the other three were gripping their seats at the rear. Huge steep walls of black waves threatened to engulf our tiny vessel as the engines struggled against the swell. I could barely see as the cold saltwater crashed continually over the bow – my eyes felt like they’d been gouged out and someone was pouring neat vinegar into the stinging hollow sockets. I was convinced that the next wave would swamp us and I was desperately trying to keep my eyes open to look for the nearest piece of land that I could swim towards. I stumbled towards the back of the boat where Rivo was struggling to stay on his feet as he fought to steer the boat. I knew how scared he and the other two were because for the first time in the whole trip, they had all put on their life jackets. I shouted to Rivo that we should turn around and head back for the coastline, but he said it was impossible to turn the boat without us capsizing. I then pointed to a small island inside the bay and said he should point the boat in that direction. He shook his head and said we couldn’t land there because there was a prison on the island holding dangerous criminals and they’d kill us. I realised that Rivo needed to keep his whole attention focused on keeping us afloat – now wasn’t the time to argue with him about flawed logic. He was trying to focus on the distant red flashing beacon of the lighthouse at the far end of the bay – our intended destination – but he kept losing sight of it as these terrifying black waves towered either side of us.

To cut a long story short, we made it, five hours later, entirely by good fortune. Once on land, we headed straight for the nearest bar and I had the best-tasting G&T I’ve ever had. I learned some months later that the word ‘Loza’ translates as ‘dangerous’. You’re not kidding! I also learned that three years prior to our crossing, Rivo had done the same night-crossing of the Loza Bay with Rick Watson, and they had experienced exactly the same problems and were also lucky to survive.

All Photos are by Ruth Tingay

All hats off to Ruth Tingay! Discussing the small number of female ornithologists recently, in Rwanda, I was told of a few — and here’s more and very abundant proof. Getting her book NOW, and forwarding this to others interested. Very nicely done “interview.”

Excellent interview on Ruth’s work and hopefully monies can be found to further long term research on MFE.